Fuelling the Explosive Sprinter: Why Track Needs a Unique Carb Strategy

Sprint performance is built on explosive power, repeatability, and fast recovery, not endurance. This article explains why sprinters cannot fuel like marathon runners, breaking down the energy systems that drive high-intensity efforts and how carbohydrate timing directly impacts power output on the track. From ATP production to glycogen availability, we explore why precise, well-timed nutrition is essential for sustaining maximal performance across repeated sprints, training blocks, and competition days, and how integrated data can help athletes identify what is really holding them back.

Why Sprinters Can't Eat Like Marathon Runners

If you’ve read our past post, you’ll have seen that we covered the basics of nutrition. Now let’s look at how we can apply this information so as to address the specific needs of a track sprinter. Track cycling sprinting is unique in the athletic landscape because it is overwhelmingly an anaerobic sport. While a marathon runner relies on aerobic endurance and fat oxidation, the sprinter relies on short, explosive power that demands instantaneous energy. This fundamental difference dictates a completely unique nutritional strategy, particularly regarding carbohydrate timing.

For the sprinter, the goal is maximizing explosive power output and maintaining it across multiple efforts, heats, and rounds, maybe across multiple days as well—all while minimizing recovery time. Nutrition must serve the on-track objectives of power, repeatability, and immediate fuel availability.

Understanding the Energy Systems

All physical activity is powered by ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate), which is regenerated through three metabolic systems operating on a continuum based on intensity and duration.

The ATP-PC System**):** This system uses phosphocreatine (PCr) to rapidly replenish ATP. It is the fastest and first to activate, lasting only 6–10 seconds. This is the system that fuels your max-velocity 50m sprint or your standing start effort. It is entirely non-dependent on oxygen and relies heavily on immediately available fuel sources.

Anaerobic Glycolysis: As PCr depletes, this system breaks down glucose without oxygen. It produces ATP quickly but inefficiently, leading to the rapid accumulation of metabolic byproducts and the feeling of fatigue. This system dominates from approximately 10–40 seconds but tapers off as decreased pH from accumulated lactate impairs enzyme activity and NAD + pathways reach bottlenecks. This results in a shift to aerobic pathways as the effort wears on.

Aerobic Glycolysis**:** This system oxidizes glucose with oxygen, generating ATP at a slower rate but sustaining effort longer. From 40-60 seconds of the effort, aerobic pathways shift from contributing approximately 40% to 70% or more of all energy utilized by our muscles powering the effort. This shows how important a strong aerobic base is in energy production. It also aids in recovery between high-intensity intervals and clearance of metabolic waste.

Bear in mind that the systems don’t work in isolation; they overlap dynamically. However, since the primary competition is dictated by the ATP-PC and Anaerobic Glycolysis systems, the sprinter’s fuel tank (muscle glycogen) needs to be constantly topped up and readily accessible.

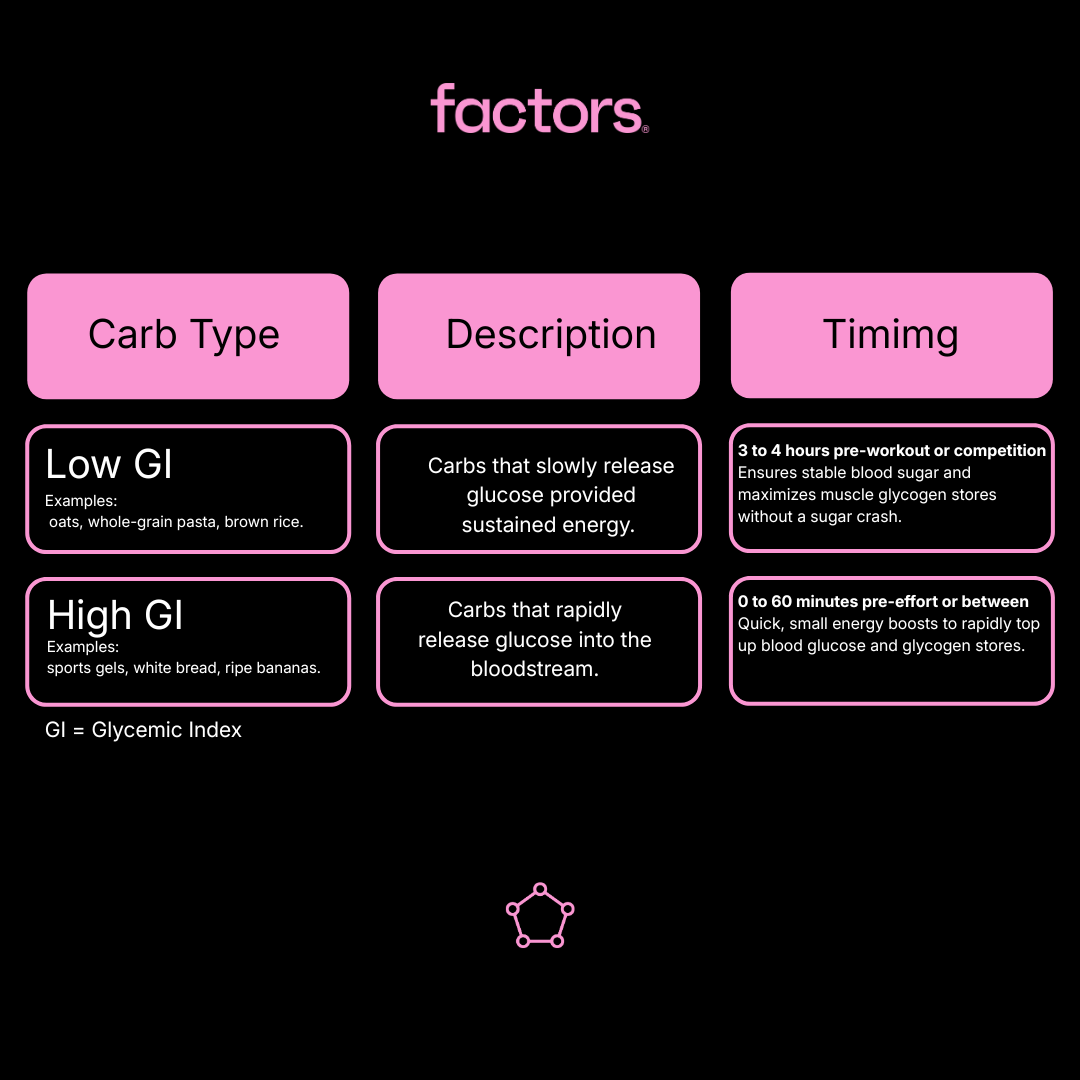

Carb Timing for the Track: Low GI vs. High GI

Due to the intermittent, high-power nature of sprint competition and training, the timing of carbohydrate intake is arguably more important than the overall quantity.

By prioritizing complex, low-GI meals hours before the session, a large reservoir of energy. Then, by using simple, high-GI snacks right before or between repeated efforts, we ensure the fuel needed for explosive movements is instantly available.

What happens if we fuel sub optimally?

We aren’t robots and most of us have responsibilities outside our training that might impair our nutrition. It’s unrealistic to assume we nail our diet every day. However, failure to meet our specific needs can be catastrophic for sprint performance. Take you eye off the ball for long enough and decreases in performance will present themselves. To name a few….

- Inadequate carbohydrate intake means the ATP-PC and Anaerobic Glycolysis systems have limited fuel, directly reducing your maximum contractile force and time to exhaustion.

- Low glycogen can impair the signaling between the brain and muscles, leading to a measurable decrease in power output and the ability to execute sharp, technical movements.

- Protein and micronutrient deficiencies slow down muscle repair, meaning you enter your next session under-recovered, leading to stagnation or even regression in strength gains.

To maximize your power output on the track, you must move beyond generic nutrition advice. The explosive demands of track cycling require a meticulous, timed approach to fuelling that keeps your limited, critical glycogen stores in a state of ready accessibility. Sometimes, the negative effects of poor nutrition are insidious—easily lost when you mix in the stressors of a full-time job, family, or academic pressure. The true origin of what's holding you back can get completely obscured. So, what’s the solution? Qualified nutritionists are the gold standard—trained to address these problems with unique, personalized solutions. However, they can be costly and often have full schedules. Factors is designed to bridge this gap: it is effective, accessible, and helps you realize the true source of what's holding you back. By designing and training our AI Coach to draw objective data from your nutrition, training, and recovery metrics, we illuminate the precise relationships between all three and how they affect one another. This integrated data makes objective feedback straightforward, allowing you to quickly identify and decisively address performance barrier.